Report

Reinventing change management in federal

The Change Agents Hiding In Plain Sight: Workforce Teams

A new Eagle Hill Consulting survey shows that according to federal employees, optimizing change is a weak link in workplace teams, which is a missed opportunity for improving mission effectiveness. Only 13 percent of those surveyed strongly agree that their teammates foster change, and just slightly more (18 percent) strongly agree that their team leader does.

A convergence of forces is intensifying the pressure on federal agencies to improve how they manage change. Citizens are demanding streamlined customer experiences. Mandates are driving transformation to improve efficiency, effectiveness and stakeholder responsiveness. Resource limitations are pushing agencies to do more with less. Emerging technologies are innovating ways of working.

Now more than ever, an agency’s ability to deliver the mission hinges on its ability to change.

In this environment, many agency leaders recognize the need to develop more adaptive organizations to deliver the mission, engage federal employees and satisfy stakeholders—from taxpayers to legislators. Many agencies have invested in traditional top-down and bottom-up change management initiatives, but these approaches do not always work. Seventy percent of transformation efforts fail, according to Harvard Business Review.

One reason for these failures is that linear, role-based approaches to change that focus solely on individual adoption do not align with how people work today—in teams. Consider that Harvard Business Review reports that employees spend 50 percent more of their time on collaborative work than they did 20 years ago. Like the private sector, federal agencies are tapping into the “collective intelligence” of multi-disciplinary teams to complete both administrative and mission-facing tasks and services.

Federal agencies have an opportunity to address this disconnect between business-as-usual change models and new ways of working to build their capacity for change. Put simply, optimizing an agency for change means optimizing teams—both teammates and team leaders—for change. The key is to make change management more networked, outcome-focused and team-based. Agencies that do this well can improve mission effectiveness, and in doing so, positively influence people’s satisfaction, trust and confidence in the federal government.

This dynamic between teams and change plays out in the sports world every day. In team sports, athletes and coaches are part of something bigger than themselves. Their job is in service of the team. The team is the tribe and the touchstone. Sports teams continuously change, and at the same time, they help ground athletes through change. Just like federal teams must do. Because when work happens in teams, they become the de facto nerve center of where change happens—or where it does not.

Teams in Sports, Teams at Work: Ability to Change a Critical Success Factor

With teams so critical to how federal agencies work today, we wanted to understand how well workplace teams are functioning today in the federal landscape.

Our survey of federal employees completed with Government Executive measures three critical elements of high-functioning teams: cohesion, performance, and continuous growth and change. As Figure 1 shows, each element is made up of key factors related to both teammates and team leaders. Each factor is essential on its own. Together, they set the foundation for a team’s success.

Figure 1: High-functioning teams have cohesion, performance and continuous growth and change.

Teammates and team leaders foster:

- Common purpose

- Commitment to team

Teammates and team leaders foster:

- Strong performance

- Capitalizing on strengths

Teammates and team leaders foster:

- Embracing change

- Continuous growth

Source: The Eagle Hill Consulting Workplace Teams Survey 2019

Winning sports teams have these factors in abundance. However, the survey results reveal this is not always true for teams in federal agencies—and that there is room for improvement:

Cohesion: Stacking hands

Cohesion is team unity, an ethos grounded in the spirit of “all for one, and one for all.” According to Carron, Brawley, and Widmeyer (1998), team cohesion is “a dynamic process” and multidimensional. This includes alignment around goals, roles and operating agreements. While a clearly defined purpose is key, only 28 percent of employees strongly agree their team has one.

The other dimension of cohesion is the intangibles, the interpersonal and social factors that bind the team together. This area needs improvement. Just 29 percent of employees strongly agree that they trust their teammates. Only 27 percent strongly agree their teammates are committed to the team’s success. And a mere 24 percent strongly agree that their teammates are highly committed to the team’s work.

Companies cannot dismiss the importance of team cohesion. Cohesion affects team performance and ability to change. Sports fans know this. They have watched dream teams of elite athletes fall and cohesive teams with less talented athletes triumph. Research published in Sport Sciences for Health confirms a correlation between team cohesion and team performance.

Performance: Shooting for the goal

Team performance is not about a collection of individual performances. It is a coordinated collection of performances where the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. It is also about the strength of the support structures that individual teammates and entire teams have behind them.

On sports teams, coaches are responsible for orchestrating these supports to get optimal performance from teams. Team leads are the coaches of workplace teams. Only about three in ten employees strongly agree that their team lead sets clear expectations (30 percent), addresses performance issues as they arise (25 percent), and recognizes outstanding performance (28 percent). Only 21 percent of employees strongly agree that their team lead helps them get better. Equally troubling, team leads are not contributing to “wins” at work. Only 21 percent of employees strongly agree that their team consistently meets its goals.

Change: Being a champion

There is no definitive answer for why workplace teams are not effectively delivering change. However, the survey suggests a trend around a lack of change-readiness and continuous improvement. Of all the factors surveyed, employees are least likely to agree that their teams enthusiastically respond to change, and only 21 percent strongly agree. Just 24 percent strongly agree that their team constantly learns and gets better. Ironically, teams’ weakest link is essentially what companies need the most to compete today.

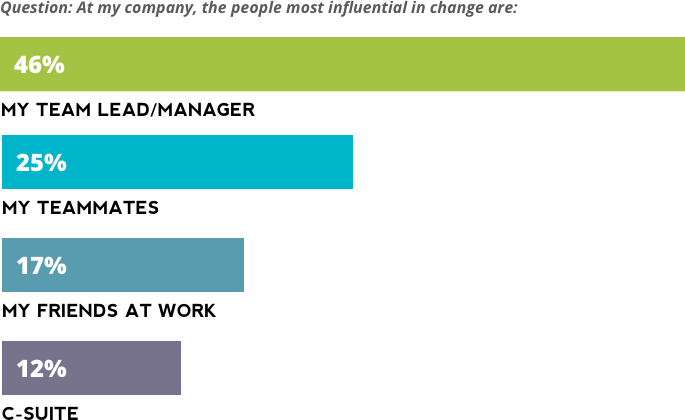

When asked who in the company is most influential in change, employees overwhelmingly point to their team lead over teammates, work friends and the C-suite, as shown in Figure 2. Yet of all the factors that team leads foster for their teams, embracing change and continuous growth rank last, which suggests that the recognized change champion is not prioritizing change.

Figure 2: Employees view team leads as the most important influencers of change at the workplace.

Source: The Eagle Hill Consulting Workplace Teams Survey 2019

This would not fly on a sports team. They have to get better, change and continuously learn. This drive to improve powers every great sports dynasty from the New York Yankees to the New England Patriots to the US Women’s National Soccer Team. In an article in Fast Company, Tony DiCicco, who coached the women’s soccer team in the 1990s, recalls what he told them when he retired. He reminded them of several memorable moments where the team experienced both extraordinary highs and crushing lows. “‘Remember all three situations, because each offers incredible motivation’.” He understood that champions do not, and cannot, stand still.

Playbook for Team-Based Change

To win in dynamic business environments, companies need a new playbook to improve workplace teams and how they embrace change. Download the full report to see the full playbook.